Costume designer Mark Bridges has worked with Paul Thomas Anderson for 22 years on a number of the director’s films, including Boogie Nights, There Will Be Blood, and Inherent Vice. But their collaboration on Phantom Thread, Anderson’s chamber piece about a mid-century London dressmaker, portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis, proved unique. “I had to be Reynolds Woodcock, too,” Bridges says. “What would a Reynolds Woodcock fashion show look like in 1955, in London, in a house of this temperament? That was a new thing, designing someone else’s aesthetic.”

As anyone who has seen Phantom Thread, which opened on Christmas Day, knows, Woodcock is fastidious, obsessive, and a sly wit, and his aesthetic is lush yet exacting. When Anderson approached Bridges about the project, he asked, “What do you know about Charles James?” The British-born dressmaker was the subject of a 2014 Costume Institute exhibition, though in the end Woodcock’s character was inspired by multiple designers. Bridges read a biography of Cristóbal Balenciaga at Anderson’s urging, and he did a close study of Hubert de Givenchy’s 1955 Lily of the Valley dress.

“We decided early on Woodcock wasn’t the greatest couturier in the world,” Bridges says. “He was going to be a man of his time—be in fashion, have a clientele, and be remembered as much as somebody like John Cavanagh, Michael Sherard, and Victor Stiebel are today.” Not one of those designers has received the retrospective treatment from the Met that James did. That Woodcock, had he been real, might have faded into obscurity alongside those other English couturiers of the 1950s makes the telling of his story no less poignant. And that’s down in no small part to Day-Lewis’s performance: “He’s so consummately in character and wanted to have some authorship with the house of Woodcock gowns,” explains Bridges. “I gave him a book of satins and said, ‘Why don’t you choose the colors for this garment?’ Paul’s all for that, and I think it worked out really well. Daniel made some great color choices.

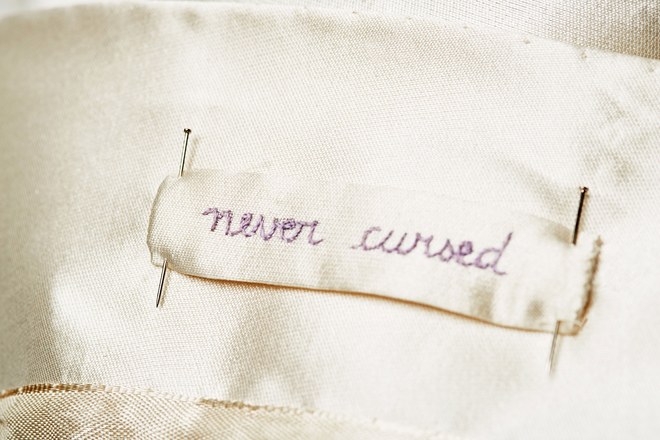

Like the movie’s protagonist, Bridges is a perfectionist, though not quite the control freak that Woodcock is. When it came time to create the lace and silk zibeline wedding dress that is itself the star of one the film’s pivotal scenes, he made it to the character Princess Mona’s measurements even though she would never wear it in the movie. His cutter, meanwhile, was dedicated to using true couture methods, so the gown was hand-stitched in real life, as it was in the movie after Woodcock stumbles onto it mid-fainting spell and it has to be swiftly remade. The dress is banded at the bust and falls to the floor in a full ’50s shape with as few seams as possible. “We listened to what the fabric would do,” says Bridges.

“I’m happy with how period it looks,” notes Bridges of the movie, “but there’s still something accessible about it. It doesn’t seem completely foreign.” Next up for the costume designer is a contemporary film by Noah Baumbach, but don’t expect anything too of-the-moment. Bridges may have recently inhabited the world of a 1950s dressmaker, but he rarely looks at modern fashion and has a staunch policy against using identifiable designer pieces in his films. “I hate this word—trendy—the way Woodcock hates chic.”

courtesy=vogue.com